The Falkland Islands experienced a major unplanned broadband outage on Sunday, 21st September 2025. From my perspective in the UK, this appeared to be one of the most severe and prolonged outages in many years. As an example of déjà vu, the scope and impact appear to be similar to those of the major outage that occurred in December 2019.

A comment on a local Facebook community page prompted me to share my thoughts on the incident.

“Seems it was not this end that caused the outage, but the other end. The [local] team here quite likely were just as frustrated as the end user was.”

This perspective rings true, and as I examined the incident more closely, several troubling concerns emerged.

How the outage evolved.

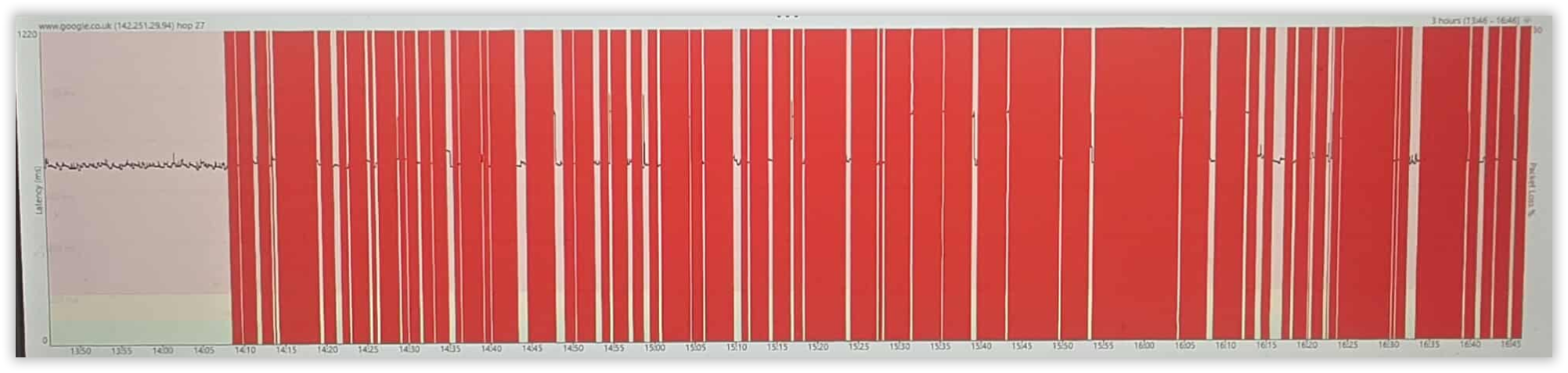

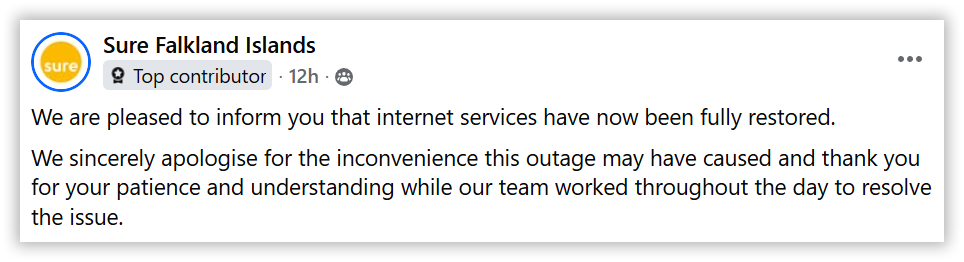

I was first alerted to the outage in the Falkland Islands by a customer, who reported that the Sure SA broadband service had been down for 2.5 hours. Based on monitoring by their PingPlotter software, the disruption began around 14:10 local time.

The 3-hour PingPlotter availability graph below shows the onset of the outage, with the timeline running left to right. The red segments indicate periods of total service loss, confirming that a serious and widespread issue was well underway.

Sure SA notified their customers of the outage at 13:57 hours on Facebook

The Chandlery supermarket in Stanley reported issues with their POS system at 15:48. As the outage was on a Sunday, it did not affect the local Standard Chartered bank, as it was closed.

Sure posted an update at 18:25 when they stated that 4G broadband connectivity had been restored using the OneWeb LEO service, which is totally independent of Intelsat’s GEO-stationary satellite services.

Sure, SA finally announced the end of the outage at 20:16, which lasted for just over 7 hours.

A UK perspective.

As soon as I was notified of the outage, I ran PingPlotter and connected to horizon.net.fk, a router in Stanley managed by Sure SA.

It was immediately apparent that the international link between the Falklands and the UK was down. Typically, the route to the Stanley server involves approximately 17 hops. This time, however, PingPlotter showed traffic bouncing through 56 different routers, and still failing to reach the Falklands.

For several hours, the traceroutes were in complete chaos, trying to reroute traffic. PingPlotter and IPlocation.net showed traffic bouncing through routers in Paris, Milan, Frankfurt, Newark, Montreal, Ashburn, New York, Washington, South Africa, Chicago, Atlanta, and Dallas, appearing and disappearing almost at random on a second-by-second basis.

Of course, it was doubtful that the route to the Falklands was actually following these bizarre paths. For technical reasons, that didn’t add up.

The evidence pointed firmly to Intelsat’s network, the system Sure SA 100% relies on to connect Falklands broadband traffic to Internet backbones in Europe and the USA. This was not a problem with the local Falklands network.

In fact, the earlier Facebook comment seems to have been right: “It was not this end that caused the outage, but the other end.”

Where is broadband service resilience?

Sure, SA relies entirely on two Intelsat geostationary satellites, Intelsat 10-02 and Intelsat 37e, to deliver broadband service from the Falkland Islands to Europe and the USA. The company operates two independent ground stations in Stanley: a 9-meter antenna linked to Intelsat 10-02 and an 11-meter antenna connected to Intelsat 37e.

All Falklands broadband traffic is routed through Intelsat’s Points of Presence (PoPs) in the USA and Europe, where it connects to the global Internet backbone via Intelsat’s terrestrial network partners.

However, the recent outage highlights serious concerns about the lack of resilience of this setup. If two independent satellite links are in place, why did a single failure result in a complete island-wide outage?

An Intelsat brochure on ‘Satellite Connectivity and CyberSecurity’ can be read here. Clearly, their advice proved ineffective during this outage.

“Where is Your Weakest Link?

Given the breadth and depth of the connectivity ecosystem, it is not enough to secure the satellite itself. Satellite networks are global and span multiple terrestrial, teleport, satellite, and other access connections. Every end-point across the distribution cycle needs to be assessed, tested, and secured.”

One would reasonably expect traffic to fail over seamlessly to the functioning satellite of the backbone link; yet, this clearly did not occur. It was more likely that the issue was caused by a problem in Intelsat’s terrestrial networks.

However, if the second Sure SA Geo geostationary satellite link had been provided by an Intelsat competitor such as SES, the outage could likely have been avoided altogether through automatic failover to the alternative satellite path, which would also have used different terrestrial connections to the Internet backbone in the USA and Europe. This is called ‘diversity’ and is a fundamental concept in telecommunications network architecture. Was this considered when the second earth station was installed in Stanley?

Even more puzzling, during the disruption, Sure SA informed customers that 4G broadband had been restored via the entirely separate OneWeb LEO service. If OneWeb was fully operational and available, why hadn’t it been configured from the outset as an automatic failover to the Intelsat geostationary service? After all, providing this kind of resilience should have been the primary benefit of Sure SA’s and FIG’s investment in the OneWeb LEO network, ensuring continuity for local businesses and preventing failures such as the supermarket’s POS systems going offline.

Both of these issues stand in stark contrast to the many recent claims about the reliability and robustness of Sure SA’s broadband service and LEO service. It certainly does not reflect well on Intelsat with their Multi-Orbit Strategy, which integrates GEO and LEO capabilities to improve resilience and diversity, a feature that was supposed to benefit Sure SA customers.

To harp back to the final comment by the presenter in Sure SA’s public presentation in March 2025:

“…as I said you really do have our attention we are working flat out and we’re determined to find a solution that addresses your concerns and brings faster broadband more reliable broadband at a lower cost as well.”

Conclusions

This September outage has yet again exposed serious shortcomings in the resilience of the Falkland Islands’ broadband infrastructure. Despite relying on two separate Intelsat satellites and operating independent ground stations in Stanley, the system failed in a way that suggests there is no workable redundancy in place. This raises uncomfortable questions about whether Sure SA and Intelsat have oversold the robustness of their services.

Equally concerning is the fact that OneWeb’s LEO service was only introduced partway through the outage, rather than being automatically deployed as a failover service. If such a backup capability exists, it should be integrated into the system to protect islanders from prolonged disconnections.

The December 2019 unplanned outage was attributed to a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack on Sure SA. Likely, the recent outage was also the result of a cyberattack (or possibly a network failure), either on Intelsat’s network, one of its partners’ networks, or one of its operational platforms. Such incidents are becoming increasingly common, and without proper redundancy planning, any disruption to a single carrier can have catastrophic consequences, as experienced on 21 September.

The fundamental issue is not the cyberattack itself, but the over-reliance on a single operator, Intelsat. The real problem lies in the inability to seamlessly switch to an independent backup connectivity service from a different upstream provider.

For a community that relies heavily on reliable communication, socially, economically, and strategically, this outage cannot be dismissed as ‘just one of those’ technical glitches that happen. It is of fundamental consequence. The residents deserve a clear plan to ensure that this scale of disruption does not happen again. Anything less undermines confidence in both Sure SA and Intelsat.

It is quite ironic that those islanders using Starlink terminals were not affected by Sure SA’s outage, which clearly demonstrates the need for independent telecommunications competition in the islands to provide true diversity.

What followed.

I’m pleased to see this statement from Sure, issued on Monday, 22nd September 2025, which highlights why resilience must be improved post 2028 through the provision of competition and service diversity in telecommunications services on the islands.

It also confirms the second point made by the commentator at the start of this post, “The [local] team here quite likely were just as frustrated as the end user was.” I am sure they were.

The good news was that the Chandlery supermarket was again able to accept card payments as announced at 16:30 on Monday, 22nd September, after switching over to Starlink.

Chris Gare, OpenFalklands, September 2025, copyright OpenFalklands

This incident demonstrates the importance of eliminating single points of failure within the Falkland Islands backhaul.

Clearly the network routing was not configured to include the backup path (via OneWeb) – so the Intelsat outage resulted in the FI dropping out of the Global Telecommunications network.

This is a useful example to illustrate the need for multiple routes – particularly for undersea fibre cable.