Update: September 28th 2022.

Although this is ‘old news’, it is still worth publishing; I’ve managed to get hold of a recording of the 10th May 2021 public meeting hosted by Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) where questions were raised about Starlink and where it was confirmed that LEOs are being treated as VSATs from a legal perspective.

Source: Falkland Islands Radio (FIRS)

Original Post.

A previous OpenFalklands post talked about the OneWeb Low Earth Orbit satellite (LEOs) constellation as the Falkland Islands will soon be within its reach.

However, the elephant in the room is Sure Falkland Island’s (Sure) exclusive communications licence and the VSAT legislation implemented by the Falkland Island Government (FIG) to minimise the use of Very Small Aperture Terminal (VSATs). (Note: The exclusive licence was issued for 12 years commencing retrospectively on January 1 2016 with a two-year notice period). This legislation disincentivises constituents from using VSATs and thus bypassing Sure’s exclusive licence. It is fair to assume that no VSAT licenses have been issued since this legislation, even though the Communications Regulator stated that interest had been shown. Which, of course, was the intention.

In 2021, FIG’s legal department informally confirmed that they consider LEOs to be VSATs. This uncontested view ensures that any use of LEOs is captured under the VSAT regulation from a legal perspective.

It is enlightening to go back and see where the legislation originated. FIG listed the options they considered available to them in respect of VSATs in the October 2016 ExCo Communications Bill 163/16.

4.4 Do Nothing: It is known that a number (thought to be between 10 and 20) of individuals provide their own VSAT despite it being illegal to do so under the current Telecommunications Ordinance. It is believed the number of people self-providing is reducing and the reason is down to the improvement in Sure’s packages. As packages continue to improve it is hoped the commercial advantage perceived in self provision will diminish. Clearly a crime which is not enforced undermines the rule of law.

4.5 Allow unconstrained self-provision (deregulation. Potentially multiple ‘self’ providers could spring up as individuals or groups. Such an arrangement would be almost impossible to regulate and the government or commercial provider would need network if adverse impact on international connectivity was to be mitigated. The existing contract with the exclusive provider is subject to a 5 years’ notice, so such arrangement could only be looked at after the notice period. During this time infrastructure is likely to deteriorate and knowledge is likely to be lost. The position after deregulation is likely to be very fragile and fragmented.

4.6 Allow greater choice of self-provision/ Non-exclusive market access. It is no doubt the case that the largest users are the most likely to choose self-provision over a non-exclusive provider reducing the market available to the non-exclusive provider. The Government has created a framework of regulation (including price controls), effectively in return for the exclusive right to provide services into the market. It is a fair summary to say that free market competition in a market is likely to be more effective in ensuring practical, consumer protection, and quality of service and price control than any Regulator. It is however the conclusion of all the advice the Government has been given that the circumstances of the Falkland Islands would not support a functional market in telecommunication and, in any event the market would not deliver the government’s ambitions for such things as consistent pricing and access to services across the Islands.

4.7 Continue with policy encouragement towards the use of exclusive provider/ Actively pursue the self-providers (Recommended): People who self-provide are not contributing with the rest of the community to the joint cost of the exclusively licenced service which theoretically makes the cost of the service per customer higher than it would otherwise be. Self-provision is not outlawed completely but is instead available to individual private users (not commercial users) at a licence fee designed to disencourage self-provision. The fee could be seen as compensating the public interest for operating outside the regime. A proposed policy statement about how this might work is set out at Appendix B. The Government could identify the illegal users and make them stop either by threatening them with prosecution or actually prosecuting them.

Option 4.7 was chosen by the Executive Council (ExCo) as the selected approach rather than banning VSATs outright which could have been problematical. The adopted FIG position was to set the VSAT licence fee at a high level to discourage private provision and use Sure’s services. Paragraph 2.4 interestingly identifies a particular concern:

“2.4 The Government has been criticised in the past for its inability to prosecute illegal use of VSAT equipment due to human rights concerns. A proposed set of policy principles (Appendix B) has been drafted to ensure that the Telecommunications licensing regime achieves Government’s desired outcomes.”

The paper further acknowledged that the approach selected could be considered unconstitutional, which is quite an admission to make in a formal legal paper.

13) There are certain circumstances where the Government not allowing individuals to make personal arrangements could be said to be unlawful. Clear examples of this are where they require services that are outside the reach or coverage of the public network operated by the exclusive provider (i.e. for non-permanently occupied buildings that lie outside the universal service obligation) or where the services reasonably required by the citizen fall outside the scope

of services commercially available from the exclusive operator.14) The Government considers it reasonable that there is an alternative to using the exclusive provider in very limited circumstances. It is nonetheless appropriate that anyone managing telecommunications is within a consistent licensed and regulated regime. The Attorney General is aware of Queen’s Counsel’s opinion that suggests a failure to recognise this possibility in legislation may be unconstitutional.

15) A resident may wish to set up operations outside the parameters of the universal service obligation which will be imposed on the exclusive provider. It may not be in the operators’ commercial interest to extend the network to cover the need (or it may not be able to do so at a reasonable cost). A resident may also have data or bandwidth requirements that cannot be met by the exclusive provider at a reasonable price.

The high fee level was determined in relation to the cost of Sure’s most expensive internet package. The current VSAT licence fee was £5,400, as specified in the September 2019 Communications (Amendment)(No2) Bill 2019 para. 5.6.3.c.

VSAT usage, even before the new legislation, was enforced by using Cease and Desist notices sent to certain VSAT suppliers. It can be assumed that these have not been rescinded. In addition, we should not forget that one of the exclusions in Sure’s Individual Operating Licence is the “Personal use of VSAT equipment”.

An exceedingly tortuous application process backed up the high licence fee. This is probably a more significant deterrent than high licence cost as it asks for a vast amount of arcane technical information that a potential licensee would not have access to. Maybe not even a VSAT reseller would be able to provide it, either. All the requirements are outlined in the VSAT Licence Guidance Notes:

CRITERIA FOR LICENCE APPLICATION (Edited)

5. The Licence is only available under exceptional circumstances and requires the Licence applicant to provide evidence to the Regulator that justifies why the services provided by Sure, the exclusive Licensee, are not able to meet their requirements.6. The policy recognises that the communication needs of the Falkland Islands are best served through an exclusive Licence and particularly to ensure the universal service obligations to the entire resident population can be met. EXCO, therefore, determined that Applicants for a non-exclusive Licence would need to demonstrate that the exclusively-licensed arrangements are not adequate. This might be because of specialist technical or scientific requirements, the services are required in an area that falls outside the coverage or universal service obligations of the exclusive Licensee’s network, or because the level of data required cannot be met within the constraints of the exclusive Licence holder’s infrastructure for example.

In practice, there are several scenarios where Sure’s infrastructure and commercial policies cannot meet a valid customer need. A VSAT business continuity service for use when Sure’s networks black out, possibly due to a Denial-of-Service attack to name but one.

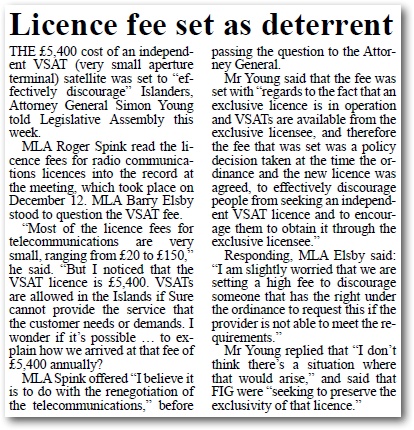

The December 13, 2019, edition of Penguin News reports on a meeting of the Legislative Council (LegCo) that demonstrates that at least one individual was questioning the impact of the legislation:

In that meeting, The Attorney General also stated:

“Mr Speaker, it’s not that the exclusive licensee wouldn’t be able to provide, I think they would be able to provide the service. I don’t think there is a situation where the exclusive licensee isn’t able to provide the service and someone is being discouraged from that it is that they can provide it within the scope of their licence to provide and obviously we are seeking to preserve the exclusivity of that licence and that is the basis on which exclusive licences are operated.”

As far as can be ascertained, Sure does not currently have a standardised VSAT product they could provide to a constituent. This is not the situation envisioned by the Regulation at the time.

A May 2021 FITV video, “Falkland Islands and Starlink: Explained“ and a 2020 OpenFalklands post focus on the legislation.

Sadly, there has been no open discussion about VSATs, LEOs or even new GEO satellite capabilities in the group supposedly responsible for the islands’ communications needs – the Technology Strategy Group. This is just as important to understand as Sure’s terrestrial and 4G networks as the broadband User Experience is wholly dependent on the quality of the satellite link to Europe.

The most recent comments about LEOs can be seen in the 2021 Regulator Annual Report.

“19. However, Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite services will continue to have a disruptive impact in the Falkland Islands that must be resolved before a way forward with the NBS can be identified with reasonable certainty. That said, the current telecommunications regulatory framework and Sure’s technical delivery architecture limit LEO exploitation without a major change to the law, Sure’s Exclusive Operating Licence, Sure’s business model and the technical laydown. The challenge will to exploit the benefits of LEO services while maintaining the viability of Sure’s current business model.

20. Sure, FIG and the public have divergent views which require careful management. Consumers, particularly in Camp, already have a strong voice. FIG and business customers do not, but LEO services may also be a good fit for their needs. Planning must consider the wider implications of LEO provider timing, the QoS of LEO services and the risks and costs of potential options. The key tests will be: is public interest promoted; are FI telecommunications improved and is the economy supported?

21. The next step will be to agree the plan, engage with Sure and ensure that public messaging is comprehensive and coherent. Action is also required to develop a better understanding of potential LEO service demand by residential, business and FIG users, and to engage with LEO providers to ensure that the use of spectrum is coordinated and that there is an appropriate use of licensing.”

Conclusions

Due to the VSAT legislation, the number of potential customers for a LEO-based high-speed broadband service in the islands is minimal. Therefore, it is highly improbable that a LEO operator could create a commercially viable high-speed Internet access business case for providing service on the islands even if the service is provided by Sure as a reseller.

Due to the VSAT legislation, the number of potential customers for a LEO-based high-speed broadband service in the islands is minimal. Therefore, it is highly improbable that a LEO operator could create a commercially viable high-speed Internet access business case for providing service on the islands even if the service is provided by Sure as a reseller.

FIG has shot itself in the foot by creating this un-futureproof legislation. The 2022 Communications Regulator’s business plan priorities include “Effective engagement in the LEO debate to protect public interests.” but It is hard to see how the VSAT/LEO legislation is in any way in the public interest today, let alone going forward.

Given that the Regulation has been validly passed under primary legislation (Communications Ordinance 2017) and represents the implementation of a clear policy decision by FIG, challenging it could be problematic. The path for a legal challenge is only possible through a judicial review which is the legal mechanism by which actions of public authorities may be challenged in court. There would seem to be quite a few supporting arguments that could be evaluated in light of the Queen’s Counsel’s concerns.

Considering that Sure has a Universal Service Obligation placed upon it which was used as the key argument behind the adoption of the VSAT Regulation to prevent revenue leakage, all monopolies have a moral obligation to provide services that meet the changing needs of their customers. Such Regulation should not be used to prevent constituent access to significant technological advances such as a 100Mbit/s+ low-latency broadband service, even if it does require a reduction in profit or revenue levels for a while.

How much longer can this legislation be tolerated in its current form? How much longer can the anachronistic legislation be justified to constituents with the limp misdirection of stating that it cannot be changed but was valid at the time it was introduced?

Will things change in the next four years with the recently announced 2022-2026 Islands Plan? Table 30, in the 116-22P: Islands Plan 2022-2026 Delivery Plan, focuses on undertaking “Review effectiveness of Regulator Role” with the following elements enumerated:

“(1) Legislative framework;(2) Regulator’s Role and performance;

(3) Regulatory and Enforcement Powers;

(4) Exclusive Licence performance;

(5) Exclusive licence renewal;

(6) Universal service provision;

(7) 999 arrangements

2. Determine Government priorities

3. Consultation and continuing dialogue with community, businesses, MPA etc. regarding needs and aspirations and managing expectations about what is achievable

4. Consider policy options to enhance ‘Digital Inclusion’

5. Instruct consultants to advise on (1) options to enhance provision and (2) to support consultations”

So there we have it. Maybe, just maybe, something buried in this list will bare fruit. Let’s hope so or it will be <7Mbit/s download speeds for the next few years while supported by the FIG £1M per annum satellite capacity support.

Copyright: September 2022, OpenFalklands

It seems that the link to Falklands blocks all internet traffic using the QUIC protocol.

Given that QUIC is a much faster method for sending webpages to browsers over a satellite link it seems a very odd situation. All the major browsers now use QUIC. And if QUIC is blocked then browsers are forced to fall back to the slower legacy TCP protocol. Making web pages slower to load.

https://stats.labs.apnic.net/quic/FK

https://stats.labs.apnic.net/quic

Thanks for this update – well worth listening to.

Unfortunately, this is totally illegal in the Falkland Islands with the legislation as it stands.

So I assume when the SpaceX Starlink MK2 overfly the FK isles no one will use their TMOBLE sim-equipped mobile phones for voice calls and text messages direct via the Starlink MK2 LEO satellite ?

No VSAT terminal required! As Starlink MK 2 will mimic a TMOBILE “cell-tower” in the sky.

As Arthur C Clark once said “one day soon good technology will seem like everyday magic”.